In a short video on the history of major league ballparks, architect Michael Wyetzner singles out the Mets’ current stadium for disapproval. Noting that Citi Field’s design was based on the iconic look of the Brooklyn Dodgers’ old Flatbush home, Ebbets Field, Wyetzner outlines all the ways the newer stadium falls short. Whereas Ebbets, he argues, was a product of the city grid, dictated by the geography of the surrounding streets and built to human scale, the Mets’ Willets Point home is bigger and more alienating and is, decidedly, not part of the interlocking urban street pattern. Lacking the “ornamentation, scale, and refinement” of its model, Citi is, in Wyetzner’s opinion, one of the worst of the new generation of retro ballparks.

The Mets’ extra-urban location, in a no-man’s land near Flushing Meadows Corona Park, was, perhaps, a more appropriate setting for their previous home, Shea Stadium. That ballpark, located next to where Citi now stands, was one of the first of a new generation of circular, multi-purpose stadiums that were often built either outside city limits or in less centralized, less densely populated areas of the city. Opened in 1964, Shea Stadium was home to the Jets until 1983 and the Mets until 2008. Shea and its fellow multi-purpose ballparks were built in response to several pressing concerns: the increasing popularity of football, the need for more spacious lots to accommodate parking, and the fears of white fans about attending ballgames in increasingly non-white neighborhoods. But the experience of these ballparks was completely different from the more intimate stadiums that came before. Checking in at Shea during its inaugural year, Roger Angell noted the vastly different character of the stadium compared to the Polo Grounds in Upper Manhattan, where the Mets played for the first two years of their existence. Failing to connect with his fellow fans in the same way, he felt that Shea was a place without “echoes, angles, and reassurance,” concluding that he and the other spectators were like “ants perched on the sloping lip of a vast, shiny soup plate, and we were lonelier than we liked.”

Less intimate than their predecessors, but still capable of raucous communion, these multi-purpose stadiums are now gone and, while once ridiculed, are remembered fondly by more than a few old habitués. In their place sits a new generation of ballpark, most of which are modeled on the first of its kind, Baltimore’s Camden Yards. Opened in 1992, Camden harkened back two generations to the so-called jewel box stadiums of the early 20th century, with its smaller scale, urban location, and brick façade, and it spawned a horde of followers, many of which lacked the intimacy and the intelligence of the original. Some of these imitators, like Citi, are remote from the city center where their jewel box predecessors sat, leading to a weird incongruity. As Michael Baumann writes in an essential article on the state of the modern baseball stadium, “It’s like putting a high-rise apartment building on a cul-de-sac,” adding that “The people who built those stadiums either didn’t realize or didn’t care that people respond to a stadium’s place in the community, rather than its building materials.” This has all led to a dead-end in the planning and design of baseball stadiums, with the most recent constructions, serving suburban communities in Georgia and Texas, standing as among the least appetizing ballparks in the game.

*****

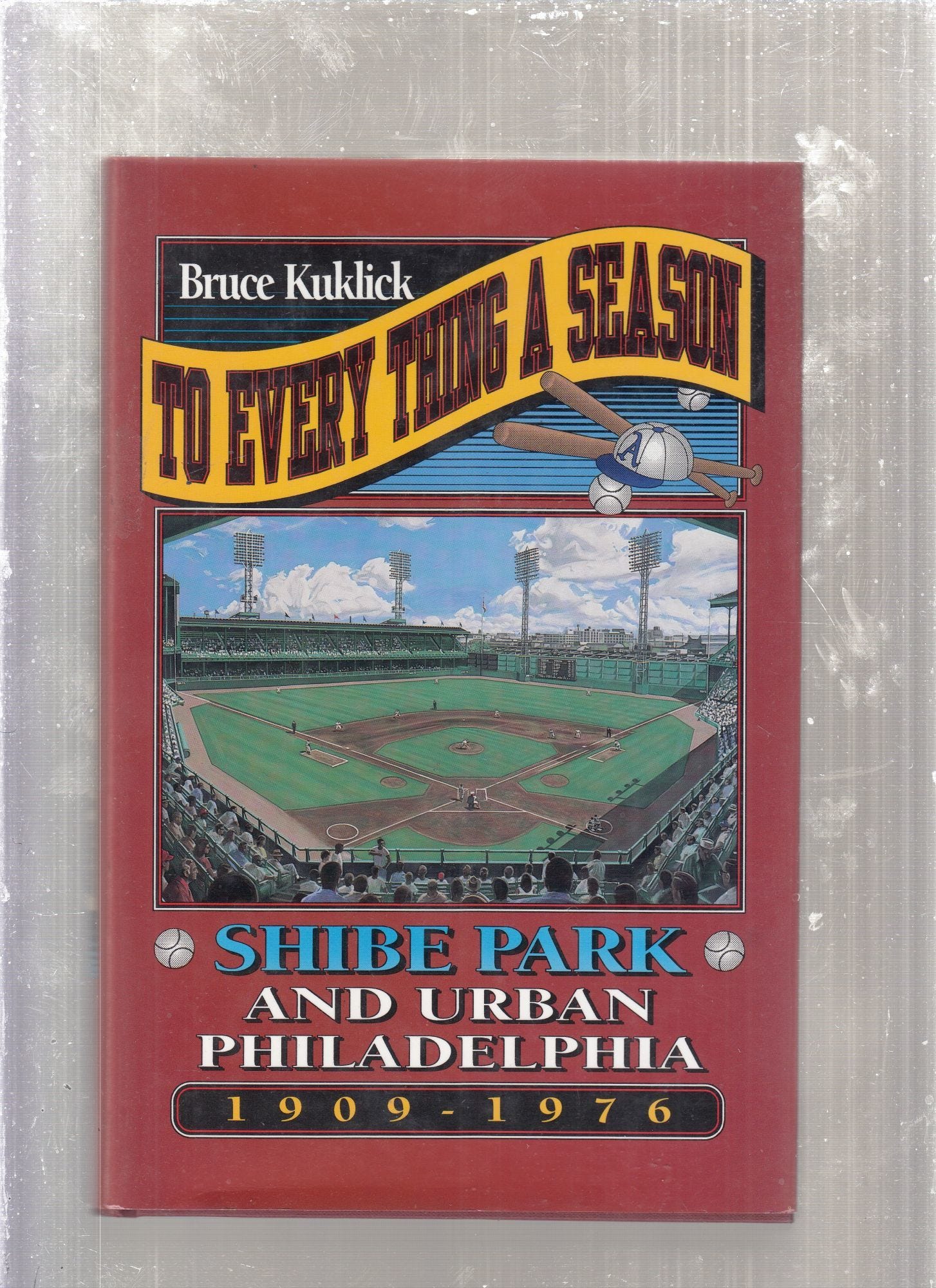

But it wasn’t always thus. “Professional baseball came of age in the early 20th century as an urban phenomenon,” states historian Bruce Kuklick in To Every Thing a Season, his eye-opening history of the now-defunct Shibe Park (later Connie Mack Stadium) and the North Philadelphia neighborhood surrounding it. “The geography of the cities shaped the parks” and the parks shared a symbiotic relationship with the people living around the stadium. In the early 20th century, Philadelphia A’s ballplayers lived in the neighborhood near Shibe, mingling with the locals. The locals attended games and themselves benefited financially from the ballpark, either by taking jobs at the stadium or opening businesses that catered to fans. Homeowners on North Twentieth Street, just beyond the right field wall, made money renting out their rooftops, which offered a full view of the game, to eager spectators, until the team finally put up a “spite fence” in 1935, ending the practice. Throughout these early years, the stadium engendered both neighborhood and civic pride. But between the time Shibe opened in 1909 and its final game in 1970 when it housed the soon-to-depart Phillies, the sport, the neighborhood, and the country changed enormously, and the team’s owners were no longer able—and were certainly unwilling—to accommodate the shifting local community.

Opening to an overflow crowd on April 12, 1909, Shibe Park inaugurated the era of the jewel box stadium. Built in a then largely undeveloped section of North Philadelphia known as Swampoodle and bound by the limits of the surrounding city streets, Shibe was the first of the new breed of concrete-and-steel ballparks which replaced the previous fire-hazardous generation of wood constructions. The design moved beyond the mere utilitarianism of its predecessors as well. Shibe featured an ornate French renaissance façade, a mansard roof, and a domed rotunda that served as the stadium entrance. Singling out Shibe as exemplary of the early 20th century era of ballpark construction, Wyetzner calls the stadium, “a real building, no longer just a ballpark,” noting that it serves as a “grand plaza” in the middle of a vibrant neighborhood. Soon other stadiums followed Shibe’s example, with classic and still-active ballparks like Wrigley Field and Fenway Park being built in the following years. By 1923, when Yankee Stadium opened, this run of classic, urban-sited, privately-financed ballparks was complete.

*****

Bruce Kuklick’s book is a social history of both Shibe Park and the neighborhood known at different times as Swampoodle, North Penn, and Allegheny West which surrounded it. It is, as Kuklick notes, not so much about the stadium or the teams that played there themselves as it is about the “feelings that people had about the park.” As he explains, people don’t simply “’have feelings’; they have them about things that are significant to them” and ballparks tend to engender these feelings in ways that other public places do not. For some people, these feelings were negative—particularly when cheapskate A’s owner/manager Connie Mack deliberately fielded non-competitive teams or, later, when Phillies fans endured decades of futility—but many more were positive. People’s attachments to a ballclub or a stadium are complicated and, in many ways, arbitrary, but those feelings are not only real but alchemic in their powers of transformation. “Men and women infuse things with meaning,” Kuklick writes. “Without the attachment of human beings, objects are meaningless.”

If the focus of To Every Thing a Season isn’t, as Kuklick claims in his intro, on “baseball, the locale, or the physical aspects of the site” where the A’s and Phillies played, it is very much about the changing character of the surrounding neighborhood. Situated on the divide between Lower North and Upper North Philadelphia, Shibe Park was in the middle of a largely working-class area, with many of the residents employed by the factories to the north of the neighborhood. Kuklick offers a detailed class and ethnic taxonomy of the North Penn area as it existed in the first part of the 20th century, reflecting on the tensions and accommodations among different groups of residents. Home largely to Irish and Irish Americans, the neighborhood also featured pockets of Italians, Jews, and Blacks. Overwhelmingly Catholic, North Penn was also home to a small, but powerful Protestant elite.

Starting in the 1950s, the demographics began to change. The demolition of houses during an “urban renewal” project in Lower North Philadelphia pushed the Black population northward, leading white residents to move further north themselves or out to the suburbs. As a Black population came to predominate, businesses left the area, leaving the community poorly underserved when it came to such essential resources as grocery stores and banks. Due to redlining, newer residents were not able to secure mortgages in the area and the housing stock began to suffer. As a result, the area around Shibe Park became increasingly poor and desperate and white fans were more and more reluctant to go out the ballpark, particularly after the 1964 uprising staged by Black residents in North Philly. This reluctance was amplified by the difficulties of finding a secure and accessible parking spot. When Shibe Park was built, most people commuted by streetcar. Later, they relied on other forms of public transportation, such as buses. But, as the automobile came to dominate after World War II, fans found parking options for the grid-bound stadium all too limited.

For these reasons, as well as his inability to increase Shibe Park’s capacity, Phillies owner Bob Carpenter began looking at new stadium options in the late ‘50s. After years of negotiation with business interests and city officials, and the floating of a half-dozen potential spots, a deal was finally struck to build a new multi-purpose ballpark in South Philadelphia, along with enough parking space to accommodate a stadium’s worth of spectators. Opened in 1971 and designed in the circular “octorad” style popular at the time, Veterans Stadium was home to the Phillies until 2003 as well as the Eagles until 2002, when both teams got new ballparks. Unlike Shibe, Veterans Stadium was publicly financed, costing taxpayers over $60 million and making it one of the most expensive ballparks built at the time. By that stage in the history of stadium construction, owners were no longer expected to raise the money themselves, instead relying on the public largesse, a dubious practice that continues to this day. Citizens Bank Park, the Phillies home as of 2004, was funded using roughly equal parts public and private funds, a small improvement. After a failed push to site the stadium closer to Center City, Citizens Bank, a handsome enough retro-style construction, ultimately ended up being built very close to where the Vet once stood, one part of a sports and entertainment complex that also includes the homes of the Eagles, ‘76ers, and Flyers, as well as Xfinity Live!, a dining and concert center.

*****

Tracing the history of Shibe Park and North Philadelphia from 1909 to the ballpark’s final demolition in 1976, Kuklick recounts the story of both 20th century urban America and 20th century sports capitalism. With minute attention to detail, digging deep in the archives to uncover legal documents, city records, and accounts of local newspapers like the long-running neighborhood rag the North Penn Chat, Kuklick shows how sports owners, city planners, and other interested parties responded to social, economic, and technological change throughout Shibe Park’s long run. In many ways, these responses amounted to a betrayal of the citizens and fans these decision-makers were supposed to serve. Whether it was A’s owner Connie Mack selling off his stars after a championship run or, more direly, urban planners dooming Black neighborhoods to isolation and a lack of resources, the story of Shibe Park and North Philly is one largely composed of self-interest, scorn, and neglect.

Kuklick’s book is a lament for the demise of both a ballpark that meant so much to so many people and of an entire era. But To Every Thing a Season was published in 1991, just one year before the beginning of a new era of ballpark construction was set to begin, inaugurated by the opening of Camden Yards. One would love to get Kuklick’s take on the Oriole’s handsome home as well as its many less successful imitators. (In a 2011 interview, he does admits to enjoying Citizen’s Bank Park but not being “overwhelmed by it,” but that’s about all I could dig up.) One thing, though, he might not like about Camden Yards: the price tag. Unlike the jewel box stadiums whose style it so lovingly aped, the ballpark’s construction and upkeep were financed entirely by overburdened taxpayers. As of 2023, between building costs, maintenance, and improvements, residents of Baltimore have coughed up no less than 1.3 billion dollars of public funds to keep the whole thing running.