“Maury would piss off God to win.”

-Lou Johnson

Setting aside the question of the almighty, Maury Wills certainly pissed off a lot of people during his long career in baseball. Among the angry: teammates, opponents, ballclub owners, and later, in a brief stint heading the Seattle Mariners—an 82-game run which filmmakers Jon Bois and Alex Rubenstein called “one of the most disastrous managerial careers in the history of baseball”—the players in his charge. The Dodgers shortstop and captain during the first half of the 1960s and the base-swiping catalyst at the top of the lineup for three world championship teams, Wills would seek any advantage to put his team in a position to win. He’d study the rulebook to dig up any obscure tidbit that might help, study the pitchers when on base for any tells that they might throw over and try and pick him off, and, when turning the double play, throw the ball directly at the head of an oncoming baserunner who didn’t get down fast enough. He’d bring total dedication to winning and expect the same from his teammates and if he didn’t get it, there would be fights. (Dodgers first baseman Wes Parker got off relatively easy. When Wills tried, unsuccessfully, to get Parker to say that he would trip an opponent as he rounded first, Parker emerged physically unscathed, the only price he paid a loss of respect in the captain’s eyes. Wills, reflecting back: “That’s the difference between him and me. I would trip somebody to win a ball game. Both feet. Definitely.”)

So not everyone appreciated Wills’ methods, but ultimately his teammates accepted them not only because Wills would do anything to avoid losing, pushing himself relentlessly and playing through ridiculous levels of pain, but, more importantly, because these methods got real results. Not only did Wills set the (since-broken) record for stolen bases in his 1962 MVP season, arguably bringing the strategy back into popularity after a several-decade hiatus, he was the team leader during one of the most successful runs in franchise history. On power-deficient teams like the 1965 world champions, he often had to do everything himself. As Michael Leahy writes in his 2016 book, The Last Innocents: The Collision of the Turbulent Sixties and the Los Angeles Dodgers, “Wills… won many games essentially alone—certainly without any meaningful assistance from teammates.” Not infrequently, Wills would get on base with a walk or single, steal second, advance to third on a ground out, fly out, or another steal, and score on another groundout. As Leahy notes, “It wasn’t unusual for him to score on no Dodgers hits at all.”

When things were going good, then, Wills earned the respect of his teammates and opponents alike, but by 1966 the fortunes of both the Dodgers and their star shortstop had taken a dip. The offseason before ‘66 was marked by multiple players holding out for a fair contract. While the team’s co-aces Sandy Koufax and Don Drysdale staged a much-publicized joint hold-out, Wills had to go it alone. The two pitchers’ demands were ultimately met, but Wills, working with far less bargaining power, was not successful in his own efforts and had to settle for the contract offered by general manager Buzzie Bavasi on behalf of the team’s skinflint owner Walter O’Malley. The season itself was an exhausting slog that, while it did result in a pennant, found the team completely spent by the time of the World Series, a contest in which they were quickly swept by the Orioles. That off-season, Koufax, tired of pitching through the pain of an arthritic elbow, announced his retirement, and O’Malley used the opportunity to clean house. Following Wills’ premature departure from a “voluntary” post-season playing tour in Japan because of a knee injury O’Malley expected him to play through, the unhappy owner traded him to Pittsburgh. With star left-fielder Tommy Davis also being dealt (to the Mets), the dynasty was over and Los Angeles wouldn’t return to the post-season for nearly a decade.

Wills himself returned to the Dodgers midway through the 1969 season and played three more years, getting released and retiring after the 1972 campaign. Then began an eight-year stint in the wilderness, with Wills working as a television analyst for NBC Sports from 1973-1977, managing in the Mexican Pacific League in the winters, and angling for a position as a major league skipper. By the time he finally got his chance, though, his life was in disarray. Enmeshed in a disastrous relationship, embarking on the early stages of what would become a major drug addiction, Wills was in no position to helm a ballclub, even a terrible one like the Seattle Mariners, where expectations would be significantly tempered. In his 1976 book, How to Steal a Pennant, a brash, entertaining plea for someone to please give its author a managing job, Wills boldly claimed that he could take a last-place club and win a championship in four years. Wills never got that chance in Seattle. Hired in the middle of the 1980 season, he would be fired less than a year later, having amassed a record of 26-56. By turns a stern disciplinarian and completely checked out, Wills repeatedly made what Seattle Post-Intelligencer writer Steve Rudman called “unconscionable strategic mistakes, third-grade sandlot mistakes,” while blaming everyone else for his errors and pissing off his players. Twenty-two games into the 1981 season, team President Dan O’Brien had had enough, sending Wills packing. And, along with his dismissal, came a plunge into a state of utter desperation. “For the first time in my life,” Wills (along with co-author Mike Celizic) writes in his 1991 memoir, On the Run, “I was faced with absolute emptiness… I had nothing to look forward to, no place to go. I had no reason to go to bed at night and no reason to get up.” The only thing that awaited Wills was the void and, in response to that void, a spiraling addiction to alcohol and crack cocaine that would last the better part of the decade.

*****

So Wills’ life was filled with conflict and unhappiness and a general sense of isolation, but not everyone was sympathetic. Among those unwilling to cut Wills the benefit of the doubt, to excuse his less magnanimous behaviors, is legendary baseball writer and pioneering statistician Bill James, who in his entry on Wills in his New Historical Baseball Abstract, seems morally offended by the shortstop’s mere existence. In an astonishing brief against Wills both as player and person, James begins by dismissing Wills’ on-field achievements. James has no truck with the claims that Wills launched the stolen base revolution. According to James, it had already begun when Wills was in the minor leagues and “did not accelerate” after Wills broke the record (emphasis his). Maybe so, but no one was stealing anything close to 100 bases before Wills did it, and soon after, Lou Brock would use Wills’ example to take the stolen base to even greater heights. Clearly, Wills had something to do with all this, but James doesn’t want to hear it. Furthermore, James is not impressed with the fact that, in his MVP season, Wills stole 104 bases while only being thrown out 13 times, citing catchers’ poor throwing skills at that time as the reason for Wills’ achievement. Finally, if James doesn’t want to credit Wills for bringing back the stolen base, he is happy to saddle him with the blame for what James considers a deleterious trend towards switch hitting in the major leagues. To which it only remains to point out that it’s hardly Wills’ responsibility if others followed his example with far less success.

But this is nothing compared to James’ obvious hatred for the man. Here’s what he has to say about Wills’ character:

Let’s face facts here: Maury Wills is a creep. He was a lousy father, a lousy teammate, a horrible husband, and probably the worst manager in the history of baseball. He’s vulgar and trashy, he doesn’t have the sense God gave a cockroach, and he blames other people for problems that he has meticulously created for himself. He’s a drug addict with an inflated opinion of his own intelligence.

Astonishing words from a man who, some might say, also has an inflated opinion of his own intelligence, but James at least tries to walk back some of these claims. “This is all true,” he writes reflecting immediately afterwards on his screed, “but it sounds worse than it is.” He cites Wills’ “hyper-sensitivity” and the difficulties of being a Black man navigating a racist world as ameliorating circumstances before lapsing right back into moral indignation. Citing a passage from On the Run in which Wills admits to having never loved his first wife and mother of his six children nor to having formed any deep emotional bonds with her, James wonders “How can you like somebody who would write something like that? You can’t.” James goes on to clarify that many people probably experienced something like Wills’ predicament but that what he finds tasteless is Wills’ willingness to admit it in public. Shifting inflection again, James ends his entry by expressing a grudging admiration for Wills’ honesty before concluding that “this may be the only thing about him which is admirable.”

*****

To be sure, what Maury Wills has to say about his relationship with his first wife isn’t nice. Throughout On the Run, Wills has a lot of things to say that aren’t nice. But the perverse sort of honesty that James both credits Wills with and takes offense at is kind of the essential stuff of a memoir. I don’t know why anyone would want to read a memoir in which the writer didn’t put themselves on the line the way Wills does in On the Run. And make no mistake, Wills knows he’s making himself look bad. This confessional reckoning with bad thoughts and bad behaviors is a large part of what makes Wills’ book one of the more compelling baseball tell-alls. Wills may not be the most introspective of men, but he cuts deeper than most other ballplayers-turned-memoirists, and he’s largely willing to interrogate his own less than generous thoughts.

For example, in an eye-opening chapter entitled “Why White?” Wills explains why, despite his attraction to Black women, he ends up dating almost exclusively blondes. It’s a chapter filled with bad thoughts, directed outwards and reverberating back inwards. After explaining that he finds Black women too “hard” and demanding, he admits he lacks both the patience and emotional maturity that comes with an adult relationship and prefers the ease he finds with white women. Reflecting back from the beginnings of his new sober life, Wills writes, “I said that black women are hard. Maybe I ought to start looking at myself. Maybe I give them reason to be hard.” It's not the most generous admission nor the deepest bit of self-reflection, but it shows a recognition that the behaviors and thoughts he’s narrated throughout the book have done no favors to either himself or those around him and that his inability to reckon with these attitudes has led to nothing but an intense feeling of emptiness.

As to the notion of liking Maury Wills that Bill James raises, this seems an odd question to pose for a memoirist. (Although maybe not for a ballplayer. Still, though, I don’t necessarily expect either breed to be particularly likable, at least in the sense that James means.) If you are looking for the agreeable Wills, though, there’s always his first memoir, It Pays to Steal, a 1963 quickie “as told to Steve Gardner.” This slim volume is actually less than half-memoir, padded out largely with filler covering everything from Wills’ thoughts on Little League baseball to a chapter divulging his (not-so-revelatory) “tips and secrets.” It’s a book devoid of personality or controversy, whitewashing, for example, the intense racial animus Wills received from fans and observers during his ’62 stolen base chase by stating lamely, “I also realized there would be some individuals who would be disappointed if I broke Ty Cobb’s stolen-base mark of 96” and leaving it at that.

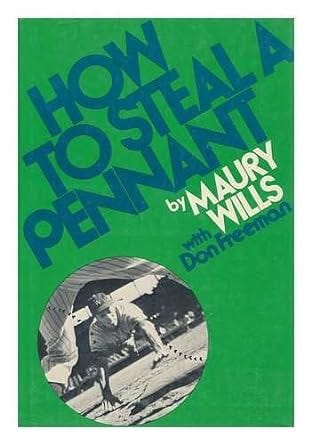

How to Steal a Pennant (co-written with Don Freeman) is more like it—although it too gets bogged down by too much back-half filler. This volume, half-memoir, half-strategy session, is concerned primarily with portraying Wills as an innovative thinker who, if he were to get the chance to manage a team, would be completely unconventional, never “playing by the book,” and constantly emphasizing aggressive play, stolen bases, and extreme levels of bunting. His prescriptions for managing a winning team are a combination of sound strategy and head-shaking notions whose absurdity would quickly earn the ire of the analytically-minded modern observer. (Have your top slugger bunt over a baserunner?! Have your first baseman play behind a speedy runner instead of holding him on?!!) What appeals (or appalls depending on your mileage) is the absolute certainty with which he puts forward his ideas, sure that he knows more than traditionally-minded managers. And, to a degree, he probably did. A ballclub managed by the brash, self-certain Maury Wills that narrates this book would be an entertaining one to watch, even if his strategizing would likely fall far short of his own high expectations. Unfortunately, Wills never really got the chance to put these ideas into practice, both because the team he inherited had precious little to work with, and, more significantly, because he was deep in a personal crisis that doomed his efforts at managerial success well beyond any questions of mere roster construction.

*****

On the Run, though, is really the only Maury Wills book you need. It’s a comprehensive volume, detailing Wills’ life and career in in-depth detail and repeating many of the reflections and events from his previous memoirs. It’s an often leisurely book, full of anecdotal asides, and in no rush to move the chronology along. At least, that is, until the final quarter, where the narrative suddenly shifts gear into continual forward motion, as Wills details his descent into a deeply troubled romantic relationship and a major addiction to cocaine and alcohol.

Above all, On the Run is a book about a man alone. Growing up one of thirteen children in Washington, D.C., Wills and his siblings were often left to themselves, their parents too busy to pay them much attention, and this sense of being on his own is one that would follow him throughout his life. Full of ambition from a young age, Wills would go to white neighborhoods to mow people’s lawns or shine shoes, his first entrée into a white world whose periphery he would occupy throughout his adult life but in which he never felt fully welcome. From the moment he left SE Washington (and probably well before that too), Wills often felt at sea, suffering from intense feelings of isolation everywhere but on the baseball fields he had been frequenting since he was a young child.

“I felt safe only on the field, in the dugout,” Wills writes, reflecting on the alienation he felt as a result of shabby treatment from the press, which significantly shaded his public perception. “As soon as I stepped out of the dugout to do anything other than play baseball, I felt uneasy.” As a result, he would go home to his apartment after games, play his guitar or banjo, drink Cutty Sark, and cry himself to sleep, as he relates in On the Run. But even on the field, he kept himself apart, never forming real friendships with his teammates. Just as he was often alone atop the lineup, making everything happen for the team, so he deliberately kept himself apart from the other players, both because he had no taste for the raucous camaraderie of the clubhouse and because, as he tells it, “I just always felt I had a special job to do, a little bit more than the call of duty. In order for me to concentrate and to gear myself up, I had to be alone.”

This perpetual retreat to solitude—as well as Wills’ obsessive and exclusive focus on baseball—had a disastrous effect on his personal life, dooming his marriage to his first wife Gertrude who left him in 1965, and causing him to have difficulty forming close connections with other women. As Wills explains in On the Run, he had never permitted himself either the emotional vulnerability or the pure level of effort required to fall in love until well after his playing career had ended, and when he finally did, the results were devastating.

After meeting the 23-year-old Judy Aldrich in 1975, Wills falls hard, entering a half-decade relationship, in which his undying obsession with his young girlfriend creates a power imbalance, allowing her to continually do him wrong, cheating on him with many different men, including his own son, while taking as much money from him as she can get. (Or at least that’s the way Wills tells it, the reader’s full level of credulity in Wills’ side of the story will depend on the reader.) By the time he gets the Mariners gig, he’s at the height of his love-fueled misery and simply can’t devote anything like the proper attention to his job. While he tries to manage, his thoughts are all with whether or not Judy is having an affair with Angels slugger Don Baylor. (It appears she is.) Unable or unwilling to be mad at Judy, he redirects his anger towards his players, overworking them and engendering a justified hatred for their new skipper.

When Wills finally gets fired from the Mariners, he’s at new low. Having lost both the job and Judy, he has nowhere else to turn, nothing in his life to sustain him. “I was defeated,” he writes. “It wasn’t just a loss. It was a devastating defeat.” Having already gotten a taste for cocaine, he now pours himself fully into his addiction, buying bundles of powder, cooking it up into rock, and smoking all day long. By his own estimate, he will spend a million dollars on the drug over 3 ½ years. He will marry another woman, a fellow addict named Angela George. He will make intermittent efforts at getting clean, and will finally succeed in 1989. And he will pass away in 2022, just shy of the age of 90, having lived over three decades clean-and-sober, still hopeful that his longshot Hall-of-Fame chances will come to fruition.

Ultimately, he will live a life defined by solitude, an inability to not be alone, even as he longs for adult communion. As he puts it late in On the Run, “I had always wanted two things—to have a real relationship with a woman and to manage in the big leagues. These were my adulthood dreams. The two things that were going to make me a complete person and fulfill my life turned out to be my demise.” Wills is far from the first professional athlete to remain underdeveloped off the field, but he’s one of the few to so publicly express a desire to alter this arrested state and to so bitterly bemoan his failure to do so. It remains unrecorded how Wills spent the last thirty years of his life, what personal triumphs and disappointments he may or may not have experienced, but the Wills of On the Run remains one of the more tragic self-presentations in sports history, a man whose intense drives were directed in a sole direction, leading him to suffer a life filled with continual unhappiness and an intense, often annihilating sense of alienation.